More Catholic historians are needed to enable people to understand God’s presence in the journey that took the Church to where it is today.

John Soniega

University of Auckland Graduate teaching assistant John Soniega, while doing his Master’s degree, found a very rich and fascinating Catholic history, which was marked by hostility at the onset against Catholic missionaries, due to both their denomination and nationality.

His dissertation for his master’s degree in history focused on how the early Catholic missionaries navigated the Northern War in 1845-1846.

“They really did occupy a very unique position due to the fact that they were French, and they were Catholic . . . in the backdrop of a predominantly British and Protestant, Anglican and Wesleyan missionary environment,” he said.

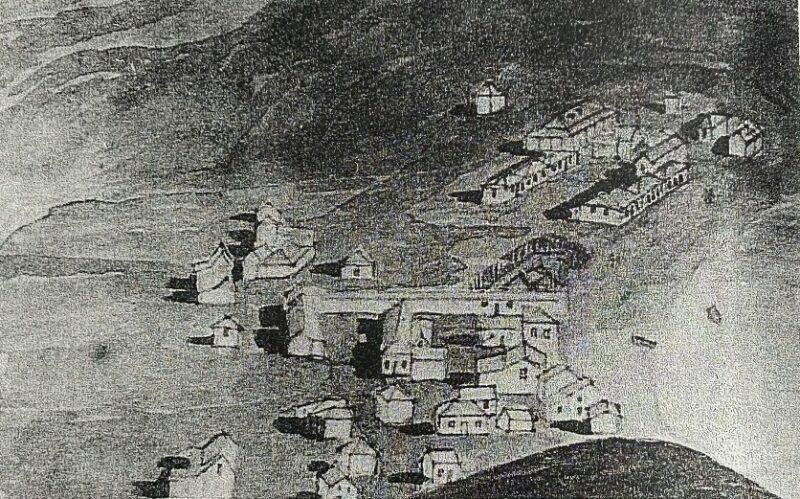

When Bishop Jean-Baptiste Pompallier and the Society of Mary missionaries arrived in 1838, “they already encountered tensions with the Protestant groups, obviously because of their Catholic teachings, and they were also under suspicion from the British government and colonial groups because of their French nationality”.

The Protestants, who were already settled and had established missionary houses, viewed the Catholic missionaries with suspicion, while the Maori people whom the Catholic priests hoped to convert already had years of Protestant Christian faith.

Mr Soniega said that the Marist missionaries took a different path to evangelisation and conversion.

“They were itinerant in the sense that they had to keep moving around Maori tribes, and had to really immerse themselves within the Maori world,” he said. “Whereas, the Anglicans and Wesleyans who were already there established these missionary houses, and they brought Maori into those houses into a more European world.”

Barely 10 years after, the Catholic missionaries found themselves in the midst of conflict between the Maori tribes and the British colonial government.

“Bishop Pompallier attempted as well to have strict neutrality. But what I found was that, for individual Marist missionaries, neutrality was very much nuanced,” Mr Soniega said.

Fr Antoine Garin, SM, for example, “was very deeply involved in the Kaipara mission”, Mr Soniega said. Fr Garin’s neutrality leaned more towards the Maori people, as he (Fr Garin) would advise them to follow their chieftains, as well as their conscience.

Fr Jean Petti-jean, on the other hand, was a priest ministering to the settlers, and viewed the Maori people with suspicion.

“Both of them deferred to Pompallier who . . . tried to remain strictly neutral, and who [had a] very reactive and defensive neutrality,” Mr Soniega said.

And then, there was the internal conflict between Bishop Pompallier and the Marists, whose vow of obedience was to the Marist Superior General Father Jean Claude Colin.

“The crisis of the war, as a pressure point, really pushed that [conflict] to the brink,” Mr Soniega said.

He added that Bishop Pompallier wanted to orient the Church to the European settlers who were coming in, while the Marist missionaries came to serve the indigenous Maori people.

“The end result was that, in 1848, after the Northern war, the New Zealand Catholic mission was split into two dioceses, one in Auckland with Pompallier, and the Marists were moved down to Wellington under a new bishop, Bishop Viard, who was a Marist at this time,” he said.

“It seemed that they (Maori) were indeed left behind because, as the Marists moved to Wellington, it was ironic that they became more geared towards a settlers’ Church as well.”

Mr Soniega said that it is important to know the “nitty-gritty details of our history as a Church”, and see how God’s providence was present there.

He said that he had always been inspired by “the saints and great Catholic men, especially how they really had that bravery and missionary zeal to go to places that were strange, alien and far from home, who were probably hostile to their faith or hostile to their nationality, and they still braved their way through to sow the seeds of the Church”.

Reader Interactions