Fr Frank Bird, SM, has seen many success stories coming out of the education work done by Society of Mary mission in Ranong on the Thailand-Myanmar border, but success generates its own challenges and more support is needed.

After ten years in Ranong as a tutor and director of the Marist Asia Foundation, Fr Bird has been back in New Zealand, where he has completed a Masters in Education at Victoria University of Wellington (Te Herenga Waka).

The title of his thesis is “Earning Versus Learning: Supporting Myanmar migrant education on the Thai Burma Border”.

Fr Bird told NZ Catholic that, more than most people, he has been privileged to see what education can do for young Myanmar migrants.

“You see them, 14 years of age, and ten years later you have been with them and they are 24. And they are the translators, health workers, teachers and leaders in their community. It has been a beautiful thing, even though it is one of the most challenging things I have ever done,” Fr Bird said of his work in Ranong.

The success stories help inspire him. He mentioned one young man who lived in poverty in a charcoal factory.

“When I visited his family, they only had one room, and I saw a blackboard on the wall. The young man was trying to learn English, and he had reached the letter C in the dictionary. The blackboard was full of words beginning with C. He was so determined to learn English.”

“He went and finished with us, he got a job at a five-star tourist resort, and he continued studying online at the University of the People in Business Administration. He has now learned Chinese, he has learned Thai, . . . he continues online learning, carrying his laptop wherever he is. Three languages, working – this is what education does!”

Fr Bird said the reason that “we are so invested in education is that’s the biggest gift we can give to a migrant community, when they are not really being able to access education. We can’t change their problems, but when they get educated, they can figure out how to change their problems”.

Already, the graduates are putting their time and energy back into their community, Fr Bird said.

“On Saturday and Sunday, our leaders, and the graduates, open up the school and have migrant outreach classes, which means the young ones who went to work in a factory at age 15 and left school, they say – welcome back – we will teach you Thai, Burmese, English, computer studies, and sewing.

“During Covid, our graduates were the ones creating facebook groups, and translating all the Thai news into Burmese and organising meals for those with Covid”.

“So our graduates are now giving back to the community.”

Factories

But most of the Myanmar migrant children still fall out the education system at a relatively young age, and end up in charcoal or fish factories. Structural issues have a lot to do with this, and that is what Fr Bird wanted to delve into more deeply in his studies.

“The Marists are really trying to respond to migrant/refugee context globally, and this is one of our migrant/refugee projects on the border, and it was about time some of us did some more intellectual understanding of the issues, so we can make sure our response is on the right track.”

He discovered that the immigration setting is in conflict with the education setting in Thailand.

“The Thai Government says – welcome to our schools, but we will not help you learn Thai, and we will not help you learn your own language, Burmese. So how successful is that going to be? You fall out very quickly.”

In the course of his studies, Fr Bird learned about education issues for migrants and refugees globally, with a particular focus on Thailand and Myanmar.

Migrants worldwide tend to be consigned to occupations that are “dirty, difficult and dangerous”.

He also came to recognise three “doors of discrimination” – which involve always having to have the correct documents as a migrant, and having real issues if documents could not be produced on demand.

“Young children may be undocumented. You were born in Thailand, you have got no ID. You have got no legal document. How can you then get a job?”

Then there is the door of the “education trap” – “if a young person is not affiliated to a government education system, they might acquire educational certificates from organisations, but it is very difficult to get recognition for them.”

Finally, there is an employment door, with limits on the occupations available to Myanmar migrants in Thailand.

“When you step back and have a ‘meta-look’ at the picture, some people call it a ‘functional failure’,” Fr Bird said.

“On the border, with the Thai Government and the Myanmar Government, the immigration policy and the education policy are not matching. There’s a functional failure, creating a lot of undocumented, uneducated young people, which is ripe for fish factories, charcoal factories, the three-D jobs.”

Better life

Despite that, parents still see education as a way to a better life, so it is highly-valued and sought-after.

“We had 175 families try to get into our primary school programme this year, and we only had 30 places available. There is so much need. Our teachers say – let us just welcome them all – and we can’t,” Fr Bird said.

But listening to Myanmar migrant teachers helped inform Fr Bird’s research.

“Migrant teachers are interesting, because they have got one foot in their own migrant community, and one foot in the education community, and they see how it is not working. So to help education, I have to make sure the ideas come from Myanmar migrant teachers themselves,” he said.

“They told me very clearly, we need to be better teachers for our children. But there is no one training teachers. So one of the hopes going back is to support teacher training, but doing it with them, not over them.”

Fr Bird said that there is a great need in Ranong for “teachers, who can then mentor our teachers”.

“The other thing is, perhaps there are schools or education-qualified people who can mentor our education, so that we are on the right track. We would really value educational support.”

One area of concern is digital technology. “If we don’t give these kids access to digital technology, they will stay stuck in factories. Now, who can mentor us in this complex pathway?”

“We are doing our best, but we are seeking professional advice and educational partnerships to actually help us.”

But as the education programmes provided by the Marists have grown – “we started with 15, went to 75, during Covid we built five new classrooms, put a new roof over the area, and we have now jumped to 280 kids” – so the need for resourcing and financial support has grown too.

Currently, there is only one computer used between five children, which is not ideal, Fr Bird said.

“It is almost like we are so successful; in a way, we are actually struggling with the demand, with the needs now.”

“Each year we seek to support approximately 80 students who come from the poorest families. We have 50 friends and supporters giving $20 per month, but as we have increased to 280 children, we now wish to find another 30 friends and supporters to ensure we can support our most in need families with transport and tuition and uniform expenses. We have a give-a-little site set up for those who would like to donate and become a friend and supporter www.givealittle.co.nz/org/maristmissionranong”

$20NZ provides a month of education for a Myanmar migrant child in Ranong, he said.

“I am at the end of New Zealanders’ generosity, seeing what it does on the ground.”

Fr Bird asked New Zealanders not to forget strife-torn Myanmar, which has fallen under the radar to some extent, with many other conflicts in the world leading news bulletins.

Fr Bird is returning to Ranong after he completes a six-month course of study on spirituality at the Teresianum in Rome.

For more information on the Marist mission in Ranong, visit www.maristasiafoundation.org or www.facebook.com/maristasiafoundation

If anyone is interested in Volunteering at the Marist Mission Ranong they can make contact with Fr Bird at [email protected] for more information.

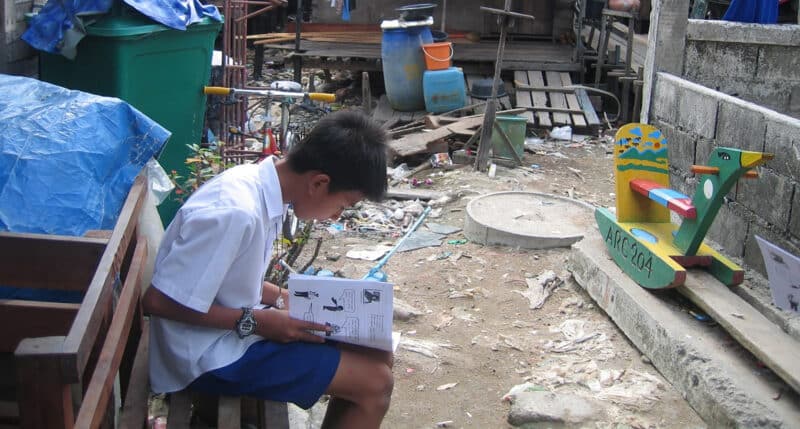

Photo: A boy from the Myanmar migrant community studies at home

Reader Interactions