As the Catholic world observed Good Friday, the Auckland Art Gallery quietly opened “Heavenly Beings: Icons of the Christian Orthodox World”, an exhibition that introduces the tradition of the devotional art of the Christian Orthodox faith.

The exhibition features 118 icons, dating from 1350 to 1800 AD. It includes devotional arts created by iconographers from Crete, Russia, Greece, Italy, Palestine, as well as Ethiopia.

Dr Sophie Matthiesson

Auckland Art Gallery senior curator of international art Dr Sophie Matthiesson worked on putting the exhibition together, with the help of Art Gallery of Ballarat director Gordon Morrison.

“It has been 40 years since an ambitious icon exhibition has been held in this country. And there would probably never be another one in our generation because they are so hard to put together,” Dr Matthiesson said.

The icons are mainly from the collection of former Australian Ambassador John McCarthy, who collected the icons “with a great eye and great respect for faith traditions, and the beauty that those traditions produced”. Two of the icons in the exhibition are from the Dunedin Public Gallery.

The eyes have it

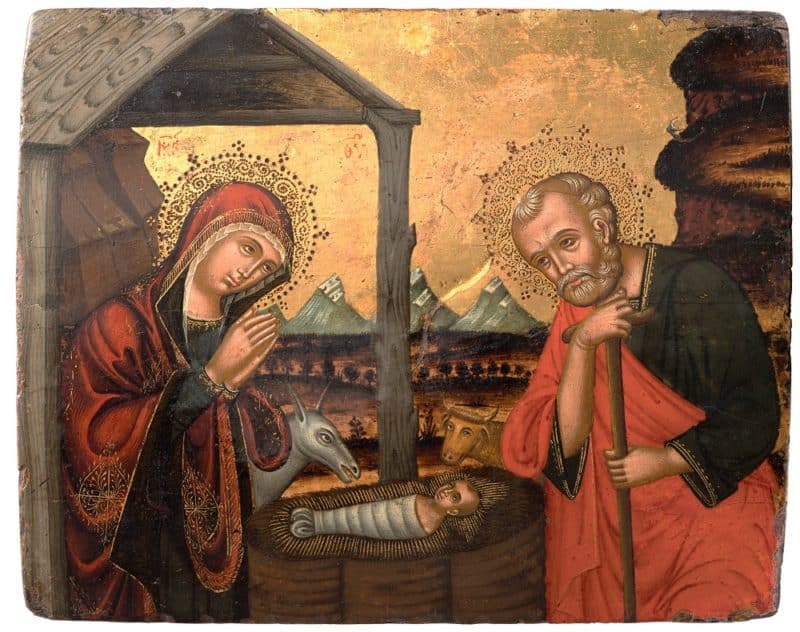

Icon of Mother of God and child. 17th century

Generally, the figures painted on icons are facing the front. The emphasis is on their eyes rather than their bodies because the eyes are the faithfuls’ access to the heavenly realm.

“They do not have to look realistic. They do not have to look like they live in the here and now because they exist outside time and place,” Dr Matthiesson said.

She explained that, to make the figures three-dimensional, “is kind of a crude idea, because we are trying to get to the essence of holiness, which is about non-materiality”.

She said the paintings of the saints are “very ascetic”, because they have a holiness that transcends the needs of the body, like the need for food.

“Their thinness and gauntness are evidence that they live the life of the spirit. They don’t rely on food. They can exist in silence for years on end. They can live in solitude. They can turn their backs on the earthly world and focus on higher things. And so that is another source of inspiration for people. It teaches resilience and faith,” she said.

Some of the faces are turned three-quarters because, when displayed, they are turning towards Christ, who would be at the centre.

The figures in the icon are also always named, because “you have a relationship of trust and mutual communication there, and you can’t be talking to the wrong person”.

A saint for a need

Devotional imagery became popular in the fourteenth century among pilgrims and religious travellers who also wanted icons in their homes.

“All the Orthodox cultures have a tradition of private veneration in the home. Icons were their primary way of doing that. In times of political stress or all sorts of displacements, you might not have a church, but [you] have an icon to pray to at home,” Dr Matthiesson explained.

“The exhibition looks at how people relied on icons in an age of belief, when there [were] not many forms of support and help that came to you.”

Sick people with no access to medicine, for example, would pray to the healing saints, Cosmos and Damian. When looking after farm animals, one might have icons of St Florus and Laurus, who look after animals. And when one is a seafarer, one would keep an icon of St Nicholas.

“And then there are saints like Elijah in Northern Russia, who seem to have some control over thunder and fire . . . very important when your lives depend on crops,” she said.

There are also icons of St Paraskeva, or the Friday Saint, who looks after marketplaces and women in childbirth, among other things.

“You can’t always pray and ask for trivial help from Christ, and Mary, the Mother of God. You go to these other figures who look after these other human needs”, Dr Matthiesson said.

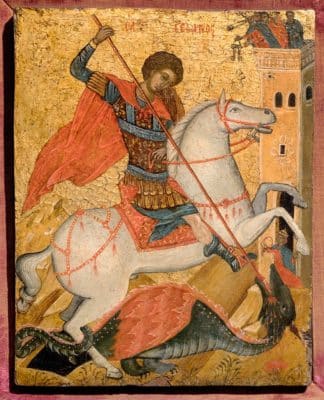

Warrior Saints

St George and the Dragon, circa 1500, Crete

Also included in the collection are Saints Nicholas and George, who are some of the most popular icons, after Jesus and Mary.

They are also called warrior saints for their fierce defence of the faith.

“Many of these saints packed a punch. They have a benevolent side, but they had an inflexible side that could withstand torture, punishment and could actually rise to violence if need be,” she said.

Saints like Demetrius and George are shown on horses with spears.

“[They are] spearing [the] infidel or the pagan king or the dragon. All of these figures that they slay are metaphors, of course, of paganism or anti-Christianity. At various times, the dragon may be a metaphor for the Ottoman empire or, in an Ethiopian icon, it may be a metaphor against the kings who are persecuting (Christians),” she said.

Dr Matthiesson said there will also be a wall that would feature martyrs, like the icon of Forty Martyrs of Sebaste, soldiers who died for their faith.

“In the 17th and 18th centuries, those martyrs became popular all over again, because there were people being martyred in the Ottoman territory and they were called neo-martyrs,” she noted.

“It’s like history repeating itself. Possibly, there will be more neo-martyrs to come. This icon has always stayed quite popular whenever there’s persecution.”

Sacred space

The exhibition will be housed in six rooms within the Auckland gallery.

The first room introduces the public to the sacred space of the Orthodox church, which includes the icon screen and the royal doors. The sacredness of the space will be heightened with music.

Each room contains some very rare and extremely old examples of iconography.

“These images are absolutely packed with history about Christianity, and how it was embraced and used and spread through the cultures of ordinary people across vast parts of the world,” Dr Matthiesson said.

The exhibition runs from April 15 to September 18. Details on admission prices and information related to Covid-19 Protection Framework settings can be found at www.aucklandartgallery.com

Why is it that this devotional art is admired and shown by a secular gallery but if this was placed in a Latin Catholic suburban ‘worship space’ would be criticized as creating a “museum”, being irrelevant, throw back, not speaking to the modern man (of 1970 who is now 80 years old) . Who is really out of touch with the transcendent? Secular curators or Catholic architects and design committees of 1970-2020?

““These images are absolutely packed with history about Christianity, and how it was embraced and used and spread through the cultures of ordinary people across vast parts of the world,” Dr Matthiesson said. ”

Bingo.

Delete these images, the prayer and routine that attend to them and the history, culture, and belief goes with it. We are all keenly familiar with the suppression of Maori culture and what that felt like. Since circa 1970 we see a renaissance of Maori reclaiming images, practices, language and subsequently a flourishing and courageous culture. An analogy to Kiwi Catholic culture is easy to make.