From his role as British naval secretary during the ill-fated Gallipoli landings, his leadership in World War II to the partition of India in 1947, Sir Winston Churchill has been the predominant personality among this year’s films.

He made no physical appearance in Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk but was there in spirit as well as voice to celebrate the safe evacuation of some 300,000 solders in May, 1940.

Churchill tracked the week or so leading up to the D-Day invasion of France four years later, as the now seasoned leader grappled with regrets arising from the Gallipoli failure.

Some dramatic licence was taken in New Zealander Alex von Tunzelmann ‘s screenplay, as Churchill is shown having doubts over Operation Overlord — to the point where he explored an alternative.

History shows no lack of commitment to victory and is the central theme of Darkest Hour (Universal), the latest Churchill film.

Nor does it show any qualms about sacrifice as Churchill, in his new role as Prime Minister from May,1940, orders a garrison in Cannes to fight to the end as a distraction for the German military from the rescue operation at Dunkirk.

The evacuation provided the backdrop for the film-within-a-film Their Finest, a romantic comedy about the making of morale-boosting features.

Finally, Viceroy’s House took an anti-Churchill stance and blamed him — in a pre-World War II role — for the plan that gave Muslims their own states on independence.

By that time, Churchill was no longer Prime Minister, so had no final say in the creation of Pakistan and its eastern territory (now Bangladesh).

Now back to Darkest Hour, which like Churchill is an account of a relatively brief period.

This is when the Conservative Party replaced Neville Chamberlain as Prime Minister in May, 1940, when Hitler’s forces were poised to push British troops out of France. The politics were highly unfavourable.

Cabinet ministers, Chamberlain and his manipulative sidekick Viscount Halifax were pushing for a rapprochement with Hitler through the mediation of Italy’s fascist dictator Mussolini.

King George VI also had doubts about Churchill’s suitability. Again as with Churchill, much is made of his uncouth domestic habits, treatment of staff and the role of his wife, Clementine, in making him more presentable.

The screenplay, by another New Zealander, Andrew McCarten (The Theory of Everything, Ladies Night), sticks closer to conventional accounts and makes more use of Churchill’s oratory and hectic scenes in the House of Commons.

Less convincing is a journey on the Tube, where Churchill meets ordinary folk in a carriage to test whether they share his willingness to resist Hitler at all costs.

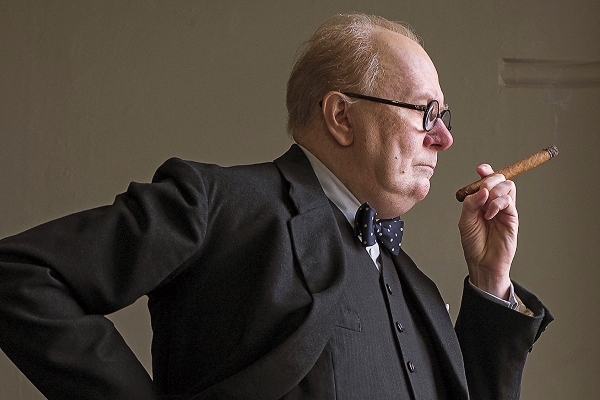

This is turned into the speech that finally banishes Chamberlain and Halifax from the cabinet and ends their appeasement plot. Director Joe Wright (Atonement, Hanna) rises to the challenge that Churchill films are primarily about performance. Gary Oldman, aided by invisible prosthetics, is superior to Brian Cox’s self-doubting characterisation in Churchill, while Kristin Scott Thomas has more gravitas than Miranda Richardson as “Clemy”. Rating: Parental guidance advised. 125 minutes

Reader Interactions