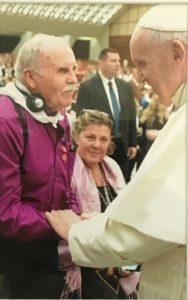

At 10 o’clock on the morning of May 18 this year, 79-year old Steve Martin found himself seated at the Pope Paul VI Audience Hall at the Vatican waiting for Pope Francis. Everything felt surreal, he said.

Steve Martin and Jo Dysart (seated, centre) meet Pope Francis.

“It was towards midday when he came. Some were kissing him and hugging him. But I didn’t do that,” he recalled.

“I was just so awestruck meeting him. And when he put his hand on me, I couldn’t say anything. I was so amazed. Here I was face to face with the Pope,” he said.

Mr Martin was one of 11 people who represented New Zealand in a meeting with the Pope sponsored by HDdennomore, a coalition of patient advocates raising awareness of Huntington’s disease and ending the stigma around it.

Huntington’s disease is a genetic neurological condition in which a faulty gene gradually causes the death of brain cells. Sufferers make jerky movements that make them appear to be intoxicated. The disease is still incurable.

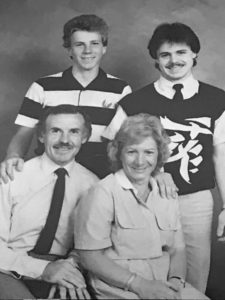

Mr Martin’s two sons, Paul and David, both have Huntington’s disease after the gene was passed on to them by their mother Margaret, who is now deceased.

Steve Martin and his wife Margaret (since deceased), with (back) their sons David and Paul, who both have the Huntington’s disease gene.

Mr Martin almost chose not to go to Rome. But he was eventually persuaded by Auckland Huntington’s Disease Association manager Jo Dysart.

“She rung me up. She said, ‘would you like to go and see the Pope? He wanted to see Huntington’s sufferers and carers.’ I said, ‘Oh, I don’t know about that. Call me tomorrow,’” he said, laughing.

She did and that was how he found himself eventually shaking the Pope’s hand.

Mrs Dysart is an indefatigable clinical nurse specialist and advocate for Huntington’s disease sufferers and their caregivers.

“It’s a terrible disorder. They call it the devil’s disease which is an awful thing to say. But there is always hope,” she said.

There is no epidemiology (study of the disease in populations) in New Zealand so she couldn’t tell how many people carry the gene.

“When I started work for them (HD Association) in 2004, they had 74 people they look after. We now look after over 900,” she said.

Asylums

Mrs Dysart said it’s only in the last generation “that we stopped putting people into asylums”. Lack of understanding of the disease often results in fear.

“If you’re blind, you’ve got a white stick. If you’re physically disabled, you’ve got a wheelchair or something. With Huntington’s disease, people can’t see the damage in your brain. Because of the movement disorder, a lot of people look intoxicated,” she explained.

She said insurance is a sore point. The cost can be so high to those who could potentially carry the gene that they might as well save their money under a mattress.

Mrs Dysart is not a Catholic. But she knew the meeting with the Pope was a crucial turning point for HD sufferers. Because of the stigma around the disease, there was no high-profile celebrity to advocate for HD sufferers until Pope Francis.

“He is the first influential person that has spoken up for Huntington’s disease. And what a first to have, eh. Follow that!,” she said gleefully.

When HDdennomore requested individuals to represent New Zealand in the audience with the Pope, she said, “It’s not about me. We need to take families.” The Hugh Green Foundation, the Neurological Association and the Huntington’s Association funded the trip for 11 people.

They brought Mary and Margaret O’Sullivan, who look after their brother and are both in a rest home together due to the symptoms of Huntington’s; Viv, a Māori lady who has symptoms of the disease, accompanied by her husband Manue; 17-year-old Catline, who is at risk developing Huntington’s; 24-year-old Chelsea who is also at risk of developing Huntington’s; Janine, whose husband has the disease and two children who are at risk of carrying the gene, as well as 18-year-old Jenna, who is a young advocate for Huntington’s and Kieran Nally, the association’s lawyer and huge supporter.

Pope Francis walked into the room and the people battling cruel stares and isolation were just infused with love.

“It was about love. It was about him sharing his love, not just with words, to the whole Huntington community,” said Mrs Dysart. “The love in that room was just so powerful.”

“It didn’t matter if you were Catholic or whatever religion or culture, it didn’t matter. What mattered was there was 26 countries in that room sharing the love from Pope Francis which indirectly made us all love each other. That was what it was about for me,” she said.

At that meeting, Pope Francis reminded everyone that Jesus, himself, “tore down the walls of stigma and of marginalisation” that isolated the sick and the suffering.

“For Jesus, disease is never an obstacle to encountering people, but rather the contrary. He taught us that the human person is always precious, always endowed with a dignity that nothing and no one can erase, not even disease,” he said.

“Fragility is not something bad, and disease, which is an expression of fragility, cannot and must not make us forget that in the eyes of God, our value is always priceless.”

The Pope spent an hour going around the room, laying his hand on heads and at times, hugging or kissing the cheeks of the patients.

“There was 300 of us in the VIP seats and from the first person he met to the last person he met, we all felt as important. He didn’t get bored. He just carried on that compassion and his presence was there all the way through which is a bit of a gift really,” said Mrs Dysart, who met the Pope wrapped in 52 rosaries which she asked him to bless, so she could take them home and hand out to some of those left in New Zealand.

The New Zealanders came out of the meeting full of hope. For 17-year-old Catline, the event was life changing. It gave her hope and enabled her to decide to go to university.

For Mr Martin, it was re-energising. “I was just flabbergasted. Just to be there to see him, that was good enough for me,” he said. Caring for his family can get tiring, he admitted, and the audience gave him a boost. “This is my mission: to look after them. I just pray that I’ll be here for as long as they need me here,” he said.

Message of hope for Huntington’s sufferers

Sir Richard Faull

Internationally recognised neuroscientist Sir Richard Faull, patron of the Auckland Huntington’s Disease Association, said there is exciting news.

“The research is showing us how we can possibly delay the disease through different types of brain stimulation . . . but most excitingly, if we can turn the gene down, we may be able to minimise the actual disease in a person and may even stop it. That’s the hope,” he told NZ Catholic.

Sir Richard, founder and director of the University of Auckland’s Centre for Brain Research (CBR), and director of the Neurological Foundation Human Brain Bank, is noted for his research into brain diseases.

“We don’t have it yet. But it’s a huge hope and we are in a position now that we were not in a position ten years ago,” he said. “We are able to provide more support, better treatment for people and we hope to be able to stop the disease altogether. Over the next ten years, we will go a long way towards that.”

Reader Interactions