by SAM HARRIS

“Society,” wrote Pope St John Paul II at the beginning of his 1996 Letter to Artists, “needs artists … to probe the true nature of man, his problems and experiences, as he strives to know and perfect himself and the world.”

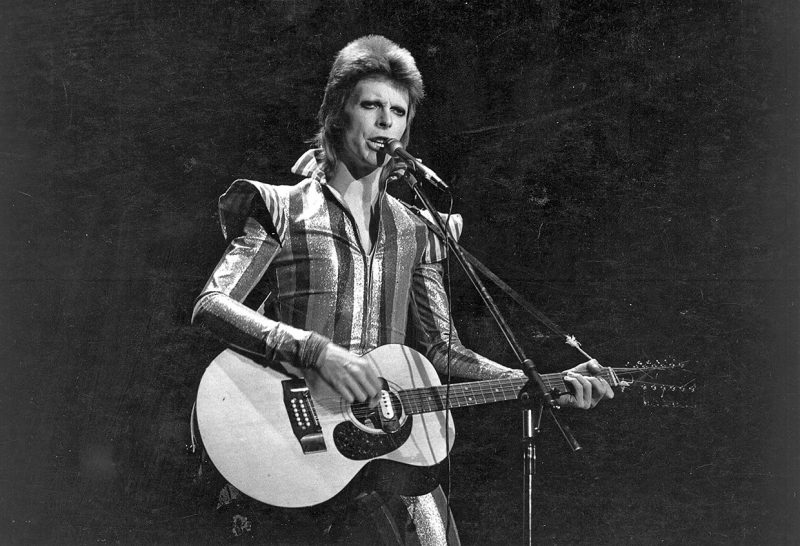

David Bowie was one artist who often spoke of his exploration of what it is to be human, and of spirituality and religion.

Bowie died last month at the age of 69, two days after releasing his final album Blackstar. Some years ago he explained, “All my life, every album I’ve made, whatever it seemed ostensibly about, under all of those things there was always a certain angle: How do I locate my spirituality? … You continue to go back to it. I think one has to try and develop a picture of what a human being is.”

This search led Bowie through some of the worst excesses of the rock and roll lifestyle — drug use, confused sexual expression, an exploration of the occult. Through this time he was a beacon for many people who considered themselves outsiders: Many tributes to Bowie after his death spoke of how his “strangeness” made them feel more able to be themselves. In later years, however, Bowie spoke of this time as “just horrible , . . falling into an abyss” and considered himself fortunate to have come through it alive.

Comparing the Bowie we see in interview footage of the time and the Bowie in later interviews (he gave very few interviews in the last 10 or so years of his life) there is a marked difference. In the early 2000s Bowie spoke of how much happier he was then, that in the 70s he was “a dreadful person”, and about how he had managed eventually to “know and perfect himself”, get at least partial answers to some of his deepest questions, and develop real relationships with people. He appears good-humoured, joyful, and self-effacing and clearly distances himself from much of what he stood for in the 70s, while not regretting what he had learnt from it and how it had shaped him. “All art does,” he said once, “is really keep you focused on questions of humanity and about how do we get on with our maker.” He went on to speak of how having a daughter with wife Iman helped focus his questions to ones that really mattered: “What are we supposed to be doing here, and how long have you got?”

These themes come through on the album Blackstar. Like much of Bowie’s work, the record is challenging, even confronting. The music is edgy, a meld of rock and jazz, with moments of tension and discordance, but also passages of great beauty. Strings, guitar, piano, varied drumbeats, electronic beeps and glitches and, most strikingly, a bold, richly textured saxophone thread through the album, and over it all is that unmistakeable voice. At times it’s peaceful, at others conflicted.

At times Bowie sings of hope, at others of despair and fear. “Look up here, I’m in heaven/. . . I’ve got nothing left to lose,” he sings on Lazarus, one of the standout tracks. “It’s all gone wrong but on and on/ The bitter nerve ends never end/ I’m falling down,” as the saxophone wails on the lush Dollar Days.

“I kind of deal with terror and fear and isolation and abandonment. I seem to have this fairly negative take on existence that I question,” Bowie said in 2002, and this still seems true on this record. The lyrics are cryptic and resist being read easily, but an alert listener will pick up on the clues in the tropes of religion, love, sex, royalty, fame, war and more.

This disc, with all its nuance and theatricality, requires repeated listens and a willingness to spend some time with a darker shade of the human experience in order to appreciate it. It won’t be to everybody’s taste, of course, but a mature Catholic will find much to like.

Again, John Paul’s words on art speak to this record: “Even when they explore the darkest depths of the soul or the most unsettling aspects of evil, artists give voice, in a way, to the universal desire for redemption.”

It’s clear that Bowie was still questioning up to his death, still exploring the depths of his soul while facing up to his impending death, but it’s also clear that he was a man who had found a great measure of peace in life by dealing honestly with the trials he’d come through. The last photo of him, posted by his wife Iman just days before his death, shows him stepping forward with a huge smile on his face.

From Lazarus again: “Oh, I’ll be free/ Just like that bluebird/ Oh, I’ll be free.” We can hope and pray that he will now rest in peace.

This is the first of a regular column on music by Sam Harris of Christchurch. Sam has the brief to write on any music that he considers to be of significance, but reading it through a Christian/Catholic lens. – Editor

Reader Interactions