There was once a time on the Chatham Islands when a Catholic priest was the only Christian minister who was there for long periods of time and, therefore, circumstances existed whereby non-Catholic Christians could receive Catholic Communion from him.

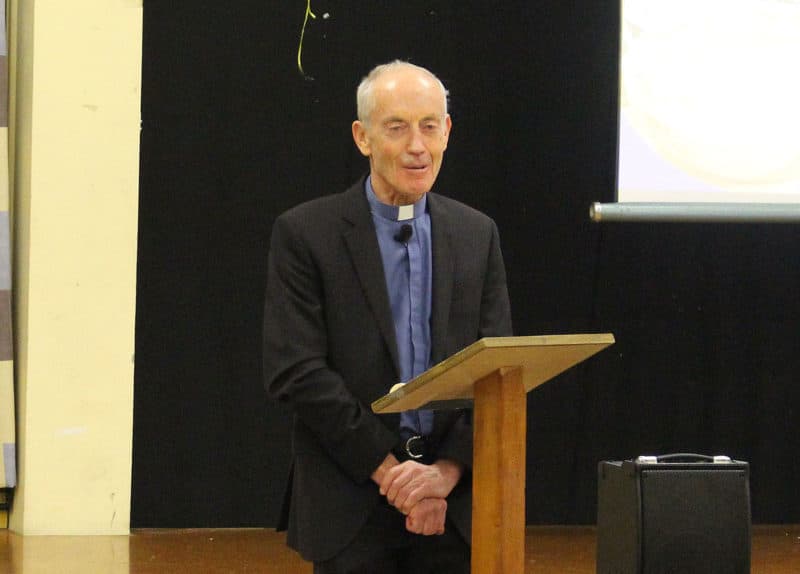

This was one of the examples cited by canon lawyer Msgr Brendan Daly in a lecture titled “The law on intercommunion with people who are not Catholics”, at Our Lady of the Assumption parish hall in Onehunga on June 22. The lecture was one of a series arranged by the Auckland diocese Commission for Ecumenism and Interfaith Relations, marking 25 years since St John Paul II’s encyclical Ut Unum Sint (That they may be one).

Msgr Daly, who is Judicial Vicar for the Tribunal of the Catholic Church in New Zealand, noted that there are now several non-Catholic Christian ministers on the Chathams, so the previous circumstances for reception of Catholic Communion by non-Catholics no longer exist there.

Msgr Daly, a former rector of Holy Cross College, Mosgiel, who now lectures in canon law at Te Kupenga – Catholic Theological College in Auckland, told the Onehunga audience that “there are many painful and difficult situations in parishes when there are celebrations of first Communions, weddings, and funerals”.

“Non-Catholic parents and relatives are often surprised that they are not given permission to receive the Eucharist,” he said, adding that “Strong theological arguments are made supporting the sharing of the Eucharist with non-Catholic spouses in mixed marriages, since the family constitutes the domestic Church.” (The family as domestic church was mentioned at Vatican II — Lumen Gentium (11)).

But the domestic church is not a church in the way an ecclesial community can be a church, Msgr Daly noted.

This is because “the Church involves clergy able to celebrate the Eucharist and the other sacraments, whereas . . . a family at home can’t do that, and in that sense they need to be part of the family of the parish, the diocese, and of the universal Church”.

Msgr Daly acknowledged in his lecture that it “is recognised that not being able to share the Eucharist with some people who are in partial communion with the [Roman Catholic] Church — Methodists, Presbyterians, Anglicans — is painful, but, from the Church’s point of view, that pain should push us to work even harder to bring about full communion, full unity with” those churches.

People sometimes justify general sharing of the Eucharist on the basis that the Eucharist is not only a sign of Christian unity, but also a means of bringing it about, he noted.

“They argue that, by celebrating the Eucharist together, the cause of Christian unity would be promoted.”

But Msgr Daly’s conclusion noted that there have been consistent statements in principle from the Church that there is an essential link between ecclesial communion and being able to receive the Eucharist.

History

His lecture covered some of the history, theology and law around the Church’s teachings on reception of Communion by non-Catholic Christians.

“Before Vatican II, it is important to remember that the Church’s law was very negative. That’s why words like ‘heretics’ and ‘schismatics’ were used prior to Vatican II.”

Before Vatican II, “a conscious non-Catholic could not receive the Eucharist unless they rejected their error, made a profession of faith, and expressed sorrow”.

But Vatican II emphasised baptism as constituting a sacramental bond of unity among all believers. Language that spoke of “imperfect communion” and “degrees of communion” was used, rather than of “heretics” and “schismatics”.

Therefore, instructions about “worship in common” (Communio in Sacris) were issued — worship which was encouraged (given suitable circumstances and the approval of Church authority) with Churches not in full communion with the Roman Catholic Church, but with a valid priesthood and sacraments.

This was not to be used “indiscriminately”, however.

Msgr Daly took his audience through quotes from directories on ecumenism and from the Code of Canon Law. He carefully went through canon 844, and spelled out the conditions necessary for reception of Catholic Communion by non-Catholic Christians, and for Catholics to receive Communion in other churches that have a valid priesthood and sacraments. He discussed exceptional cases where there is danger of death, and of refugees separated from their normal church communities for long periods of time.

“In summary, the 1983 Code requires that the individual non-Catholics must be unable to approach ministers of their own community. The impossibility may be moral or physical . . . . The non-Catholic must request the sacrament freely on their own initiative.”

Canon 844 #4 also states that these non-Catholics must demonstrate the Catholic faith in respect of these sacraments, and must be properly disposed.

In such cases, physical impossibility might mean “they just can’t get to their own minister, or they can’t locate him, when they are seriously ill”, Msgr Daly said.

“A moral reason might be — when someone has been sexually abused by a minister in that church, they don’t want to go near one, that would constitute a moral reason to approach a Catholic priest,” Msgr Daly said.

The 1993 Directory on Ecumenism strongly recommended that diocesan bishops establish norms for judging situations of grave and pressing need.

Full Communion

However, although there can be exceptional circumstances, the Catholic Church’s basic position is that people should be in full communion with the Church before receiving the Eucharist. The two go together, Msgr Daly said, citing the 1993 directory and the teachings of St John Paul II in his 2003 encyclical Ecclesia de Eucharistia.

“A sacrament is an act of Christ and of the Church through the Spirit. . . As well as being signs, sacraments — most especially the Eucharist — are sources of the unity of the Christian community and of the spiritual life, and are means to building them up.

“Thus, eucharistic communion is inseparably linked to full ecclesial communion and its visible expression,” the 1993 directory stated in paragraph 129.

St John Paul II’s basic principle was that “the Eucharist builds the Church, and the Church makes the Eucharist”, Msgr Daly said.

The 1993 Directory on Ecumenism addressed the situation of a mixed marriage: “Although the spouses in a mixed marriage share the sacraments of baptism and marriage, eucharistic sharing can only be exceptional, and in each case the norms stated above concerning the admission of [a] non-Catholic Christian to eucharistic Communion, as well as those concerning the participation of a Catholic in eucharistic Communion in another church, must be observed. [160]”

Msgr Daly went on to discuss recent efforts in Germany to permit Protestants, especially those married to Catholics, to receive the Catholic Eucharist regularly — and the responses sent by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, with the backing of Pope Francis.

While the German bishops’ efforts on ecumenism were praised by the Holy See, there are several issues at stake — including implications for the universal Church and ecumenical relations with other churches, and the need for collegiality among bishops.

Further exchanges between the Holy See and Germany last year led to the CDF emphasising that “significant differences in understanding of the Eucharist and ministry remained between Protestants and Catholics”.

“The doctrinal differences are still so important that they currently rule out reciprocal participation in the Lord’s Supper and the Eucharist,” the CDF said.

Msgr Daly concluded his talk by stating: “The Catholic Church allows sharing the Eucharist with baptised non-Catholics only to meet ‘a grave and pressing need’ of the individual non-Catholic, and not to bring about intercommunion”, which happens where two or more Churches, through an agreement, decide that there is sufficient unity of faith to permit members of each Church on a normal and permanent basis to receive the Eucharist in each other’s Church.

“While the sharing of the Eucharist is a difficult pastoral problem that many people make up their own minds about, the issuing of many norms does not solve all the problems.

“Delicate pastoral responses and more education about the reasons for the norms are necessary,” Msgr Daly concluded.

Reader Interactions