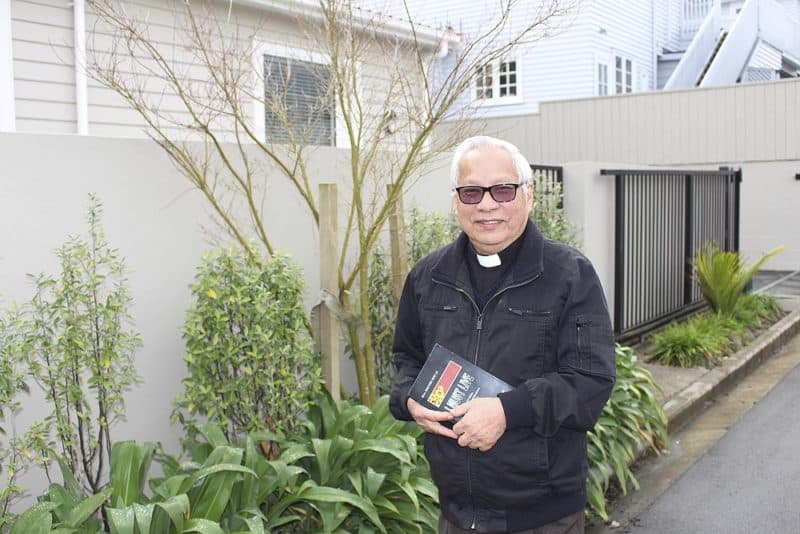

A classic of Vietnamese “gulag literature”, written by an Auckland-based Catholic priest, has been updated, translated into English and republished this year to coincide with the priest’s golden jubilee of priestly ordination.

“I Must Live” by Fr “Andrew” Nguyen Nuu Le, is an account of the 13 years he spent in communist re-education camps in Vietnam, from 1975 to 1988.

But it is more than a listing of details, incidents and dates – it is also a reflection by the priest on how God’s providential love was present throughout, enabling Fr Nguyen to be an instrument of God’s love and mercy in desperate situations. It was a providential love which, in time, enabled him to forgive those who had harmed him. There were even friendships formed, with generosity and kindness shown. It is a testimony to the deep faith of a Catholic priest who refused to be “re-educated” along communist lines.

That said, the book is a harrowing read. There is “baking” heat, with the priest being in a windowless cell with several other men with the air so hot that breathing is an exhausting struggle. It is being in a prison – the so-called “Gate of Heaven”, near the Chinese border – that was so cold that some men “howled like wolves”, before falling asleep from exhaustion. It is being shackled in a punishment cell in “the bottom of hell” at Thanh Cam camp, and having to live for weeks in one’s own excrement, cleaning oneself with one’s hand and using clothes to clean those hands. It is reeking of the smell of faeces and urine, to the degree that even a fellow priest could not stand being too close. It is being tortured, beaten, starved, nearly dying of thirst, being naked. It is seeing another prisoner’s eye cut out. It is hearing of fellow prisoners’ plans to eat you. It is seeing a friend beaten to death and having his corpse thrown on top of you, so that you can’t breathe.

And for much of this time, there was no end in sight. That was the cruelty of the re-education camps. There were no fixed sentences, which one could count down. There was just the vague promise that, if one was successfully re-educated, one would be released. Hope was distant country.

But Fr Nguyen’s camp dossier had chilling words stamped on papers: “With disposition that cannot be re-educated”. This determination was why his incarceration was so long.

Fr Nguyen, who spent two years in a refugee camp in Thailand, before coming to New Zealand in 1990, at the invitation of Bishop Denis Browne to be chaplain to the Vietnamese community in Auckland, was one of many of his countrymen who endured “re-education”. From 1975, some 400,000 people were put through the camps.

Accounts of life and death in these camps have been written over the years, but Fr Nguyen’s book, which was first circulated on the Internet and was then published in book form in 2003 in Vietnamese in the USA, became a “best seller ever”. It ran to 45,000 copies.

Meeting

Fr Nguyen told NZ Catholic that the book became much more widely read after publicity in 2004 of his meeting, eight years earlier, with “the guy who killed me” in Thanh Cam camp – Bui Dinh Thi. Thi had been one of the detainees responsible for enforcing camp discipline. A Catholic parishioner, he murdered two men who had been with Fr Nguyen in a failed escape attempt, and he tried to kill the priest too. He beat one of the men (Diep) to death and starved the other one (Vanh) until he died. He dumped the former’s body on top of Fr Nguyen.

Among Bui Dinh Thi’s many acts of violence against Fr Nguyen was this: “Then the guard seized me, punching my belly, making me fall backwards. Bui Dinh Thi punched me forwards again and so they continued like two soccer players using me as a ball.”

In 1996, Fr Nguyen met Thi in the United States and forgave him. The priest showed NZ Catholic a photo, which has him holding the hand of his nemesis, with Bui Dinh Thi’s family smiling for the camera.

Fr Nguyen told NZ Catholic that he asked Thi a question – “why did you try to kill me?”

“We had nothing to do with each other before? . . . I am a priest and you are a parishioner – why have you tried to kill me?

“He bowed down his head for a while and he said, Father, it is very hard to say. I said that is OK – but if you cannot answer my question, this question will follow me to the grave.”

The accounts in Fr Nguyen’s book led to Bui Dinh Thi being reported to US authorities. Fr Nguyen was to testify against Thi in court and he was deported back to Vietnam in 2004. But because there was no treaty between the US and Vietnam to enforce this, Bui Dinh Thi reportedly ended up in the Marshall Islands, where he is said to have died in 2011.

Fr Nguyen’s 13 years in the camps left him with impaired vision in one eye, with leg injuries which prevent him from walking freely, and with reduced use of one lung. But he doesn’t feel bitterness towards the guards and the prisoners who harmed him.

As he explained in the book: “Over a long time, especially the three years writhing at the bottom of hell in the disciplinary cell of Thanh Cam camp from 1979 to 1982, [this] gives me a well-founded stance for saying that, in each person, there are equal parts of good and evil, developing according to the living conditions. . . . In prison, I witnessed and endured the cruel and malicious actions of a number of prison guards, as well as those of treacherous fellow prisoners. I know that it was partly due to their cruel nature. However, if there was no nurturing and encouragement by the regime, then those actions would not have occurred, or if they did, they would not have reached such degrees of extreme cruelty.”

He added: “Never condemn a human being, never destroy a human being but, at any cost, wipe out any repulsive regime that encourages and nurtures hostility among humans. Replace it with a healthy society, so that humans can get to develop their righteousness and integrity.”

Mission

His time in the camps gave him a renewed appreciation for his mission as a priest. Eventually, he came to hear God’s voice telling him there was a mission for him there.

“In Vietnam,” he told NZ Catholic, “the role of the priest is very important, especially in jail. For a few years, I was the only priest for maybe 1000 prisoners. Most of them are Catholics and they looked at me as the one they hoped to stand for what it right and to be the witness to the love of God in jail.

“I thought – I can’t do this, . . . but, in jail, the priest is the chosen one, to be the beacon, to strengthen their faith and make them hope and be happy and make them feel they have something to lean on.”

Fr Nguyen was able to celebrate Masses from time to time in the camps, as parishioners would smuggle in bread and wine, sometimes disguised as medicine for prisoners. He would teach other prisoners and did some baptisms.

As he looks to the future for Vietnam, where the history of the people goes back 4000 years, this history and the character of his people give him hope that communism will not last there forever.

But he acknowledges, with sorrow, that he may never see his homeland again. He once got as close as Thailand, where he “cried a lot”.

“I never accepted the communist regime,” he said, “so as long as they are still in power, I cannot return home.”

“But I live here. My body is here, my heart is in my homeland.”

But he does not complain. He is against complaining, as he stated in the book. When the text reached the lowest point in his life, when he was desperately struggling to breathe in a cell so hot it was like an oven, he suddenly addressed the reader: “I would tell everyone that: You don’t know you are living in paradise. Never open your mouth to complain.”

Fr Nguyen is keen to publish the English translation of the book in New Zealand, if possible, and would welcome approaches from publishers who might be interested. He can be reached at: [email protected]

Reader Interactions